YYYYMMDD >>> BACK HOME <<< >>> SELECTED FEATURES <<< >>> HIDDEN ARCHIVE <<<

[20220511]

THE LAST COWBOYS by EVA GOLD at GINNY ON FREDERICK [from 20220409 to 20220522]

[Photos: Stephen James]

Sex is a city of ghosts. Its presence is felt everywhere, but only as a spectre. In flesh we have only empty spaces. Sex has become a conceptual space of contemplation. We walk around its marble halls and take in the bodies, the holes, the actions, and contemplate our feelings about them, as though they were paintings of famous men and battlefields and prize bulls. “What is it that makes this cotton against the skin so alluring to me right now?” or “how do I make her want me like I want her?” We move to the next room and spend a moment musing on the violence or the worship or the arrangement of fingers and mouths and genitals and wonder what it says about us.

But the sex itself is the spectre. “Sex” is everywhere: it proliferates in all its representations. From billboards women seduce men. On television men seduce women. On smartphones scrolling screens depict flesh after flesh after flesh. Never have we had such immediate access to the language and imagery of sexuality. Yet despite this, sex, sex itself, in a social sense, has been eradicated. There has never been a moment in human history where actual sex, sex one might stumble upon, has been so clinically absent. The past 150 years has seen a society-wide policing operation conducted by the state and moral consensus to remove sex from everywhere but the private, domestic space. Sex is restricted to the borders of the bourgeois home, to the bedroom. Happy couples no longer couple happily in the park’s summer twilight, queer people no longer catch the eye in the cinema toilets. Even to suggest that the unexpected sight of sex is not inherently traumatising is enough to label oneself a sex criminal. Sex is excised tissue from the social body, present only in its absence.

Yet we can’t and don’t live our lives, sexual, emotional, and political, as atomised individuals, with discreet desires in discrete little bedrooms. The writer Samuel Delany notes in his memoirs that “whether male or female, working- or middle-class, the first direct sense of political power comes from the apprehension of massed bodies. That I’d felt it and was frightened by it means that others had felt it too. The myth said that we, as isolated perverts, were only beings of desire, manifestations of the subject (yes, gone awry, turned from its true object, but, for all that, even more purely subjective).” Eva Gold’s sculpture Cowboys, a row of thick black crypto- leather jackets hanging from the wall, also suggests this presence in what they lack: men to wear them. Constructed from industrial building materials - the stuff of roof linings and waterproofing - they speak to the heavy, haunting presence of sex, of the potential of many bodies in contact with each other, like men at a urinal trough. That potential is erotic, political, even spiritual; to reimagine how we interconnect.

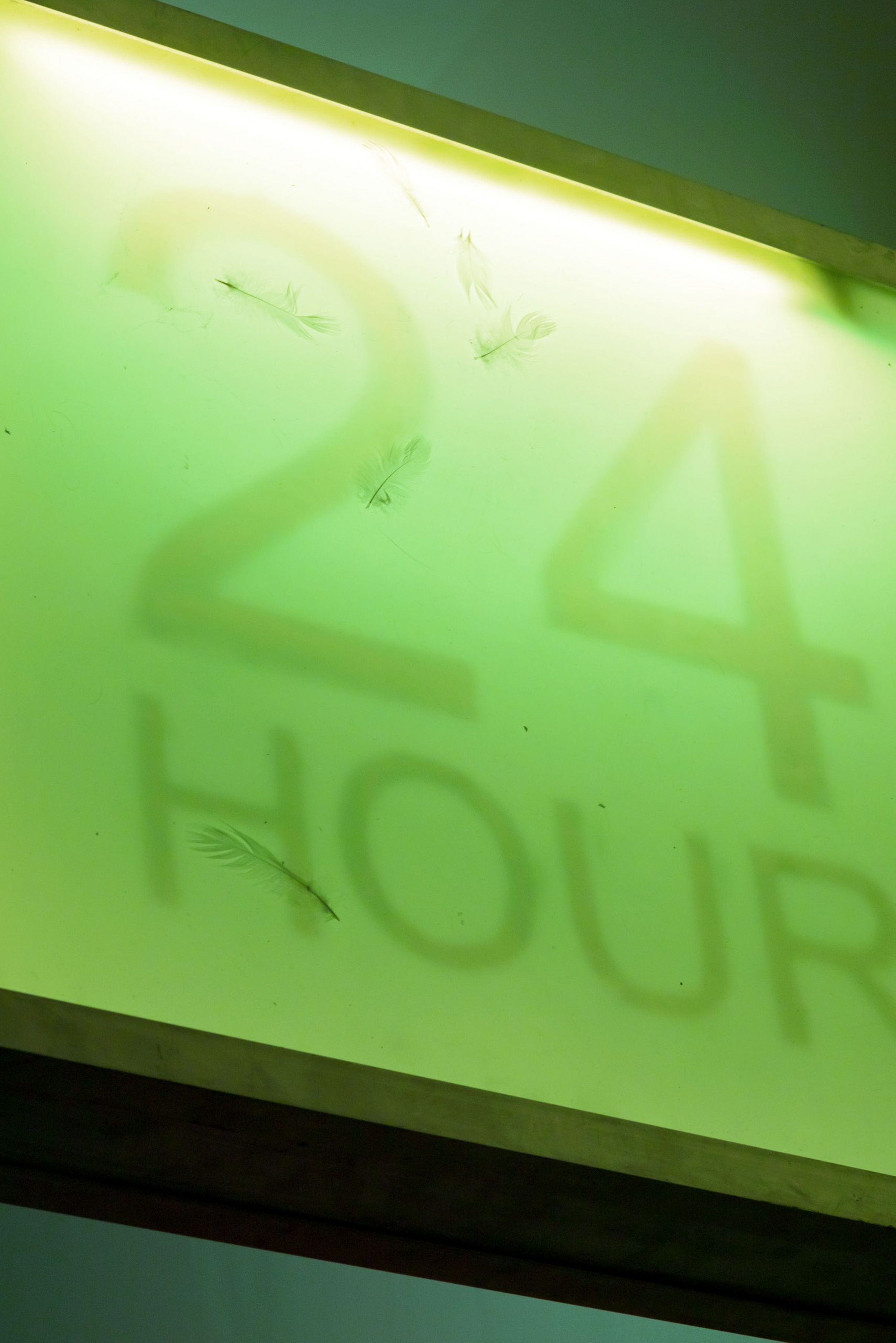

The thick membrane of Gold’s coats should reject osmosis. In its intended industrial form, as roofing, it rejects the fluid and forces it in other directions. In these massed ghosts, however, it suggests something more fungible, a sexual spectre of the possible, of the night that’s yet to come. That’s what is really at play here, this suggestion of desire in the absence of bodies. And that’s not to knock it; apprehension, hope, expectation are all the building blocks of sexual desire in the first place. The spaces that make up a city’s temporary sexual infrastructure (abandoned industrial buildings, piers, meatpacking districts, butcher’s fridges, one-night fetish nights, rented basements, saunas) are all empty sites of the sort of hope that makes your heart flutter. It’s also the case that while these spaces grew from the exclusion of a certain type of man, they operate through the exclusion of others. Knowledge of these spaces passing across culture through word of mouth and reputation, through their often romantic depiction by men who have frequented and valorised them, a ghostly apparition of an intense sexual libertinism enjoyed only by a few, but both craved and feared by wider society. In Cowboys the hunched mass of men might threaten you, and not only with a good time. Residual Heat, meanwhile, hints towards these haunted spaces, towards what and who is to come, as we duck in from the pavement and down the narrow stairs from the neon-lit street into the darkness, paying our entry to the smells and tastes and touches of actual bodies that will finally animate, incarnate, our long-formulated desires. Perhaps the ghostly invitation of the illuminated sign, advertising nothing more than a hope of sex, is what we really flutter towards To paraphrase Walter Benjamin: “The genuine advertisement hurtles things at us with the tempo of a good film... What, in the end, makes advertisements so superior to criticism? Not what the moving red neon sign says -- but the fiery pool reflecting in the asphalt.”

[Text: Huw Lemmey]

©YYYYMMDD 2021 All content and design by Daniela Grabosch + Ricardo Almeida Roque unless otherwise stated. Images, Videos and Texts can only be used under permission of the author(s).