YYYYMMDD >>> BACK HOME <<< >>> SELECTED FEATURES <<< >>> HIDDEN ARCHIVE <<<

[20220330]

MOMMIE DEAREST by JASMINE GREGORY at ISTITUTO SVIZZERO (MILAN) curated by GIOIA DAL MOLIN [from 20220211 to 20220403][Photos: Giulio Boe]

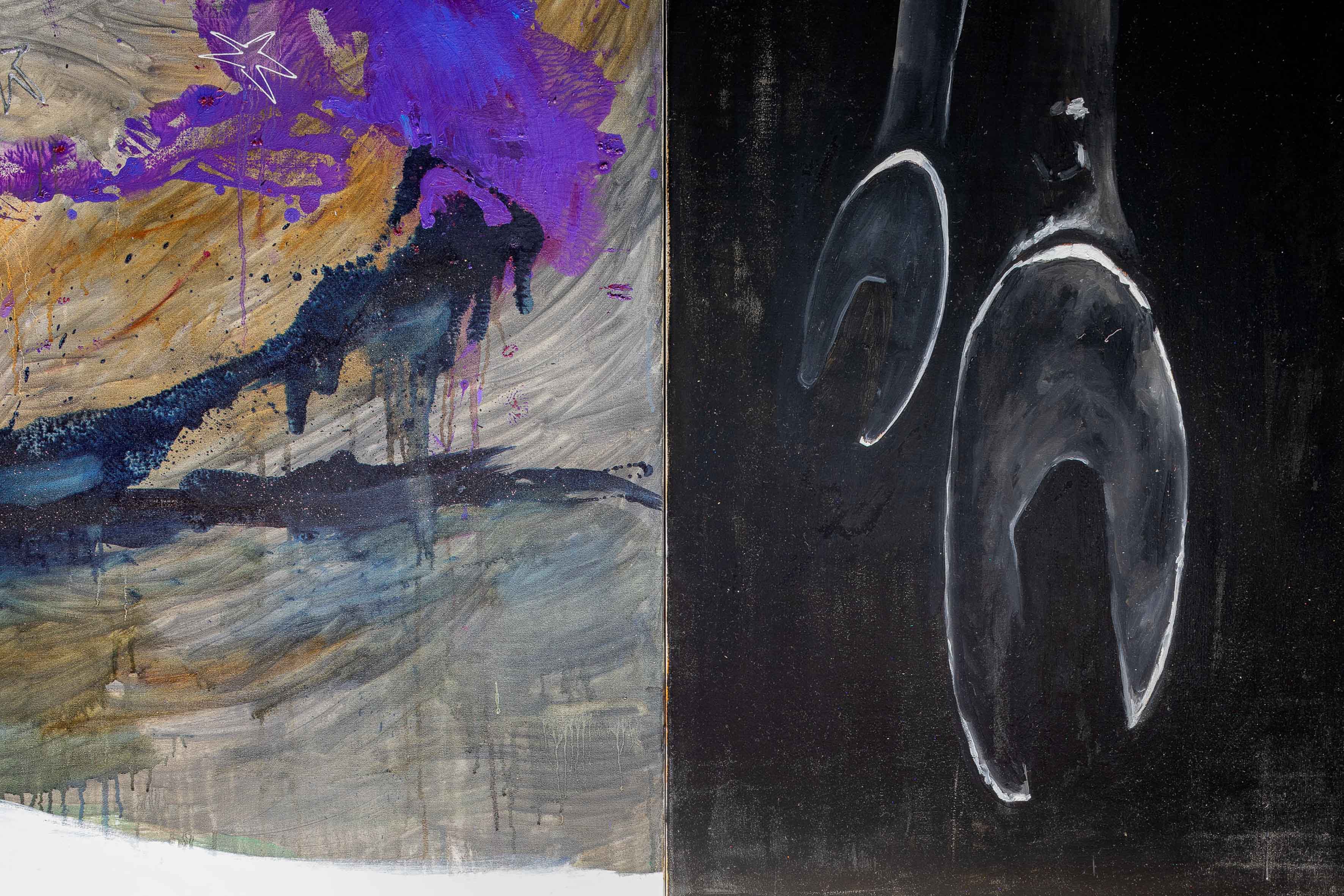

When I think of Jasmine Gregory’s work, I think of a dog with human hands and long green and pink, pointy gel nails. A bit snooty, a bit bored, its face turned slightly to the side and almost hidden under the wide brim of a purple hat—this same dog now looks back at us in Jasmine Gregory’s exhibition in Milan. Call Me Ms. Bitch, Because I Don’t Miss, Bitch is what the artist calls the painting. She came across the quote on Instagram, it echoes a line from a song by the rapper Nicki Minaj, while the composition is reminiscent of a baroque portrait. In early January, I visited Jasmine Gregory in her studio on the northern outskirts of Zurich. An unexpected snowstorm clouds the view of the world. We discuss our views on art, which may not be clouded, but certainly socially determined. The dog portrait leans against the wall, already packed, while we look at the triptych Self Giving Birth Ever Miscarried. The two works, both created last year, clearly attest to the range of Jasmine Gregory’s painting and her fascination with the medium, its cultural and historical connotations and societal impact. Figurative painting holds as much fascination for her as the rapid brushstrokes and colours of more abstract approaches. «Maybe I’m a conceptual painter», the artist muses, and maybe these stylistic labels are not that relevant when considering her work. Let us return to her studio and the triptych—which in its symmetries evokes a Rorschach test, and whose centre canvas shows a tool, representing a moment of disruption for the artist. Meanwhile, the fluorescent green might refer to the “green screen” compositing technique used in film and video to combine a background image (also digitally animated) with a different foreground. In fact, the two large canvases—just like the folding images of the Rorschach test—were created using a transfer process. Their similarities with the Rorschach test—a tool used in psychology to analyse a person’s personality, in which the subject interprets pictures associatively—go beyond the visual level. What interests Jasmine Gregory is how images are perceived, how social conditioning impacts how we view and interpret paintings, questions of references and localization, and the tensions between “copy” and “original”. This brings us to the heart, or perhaps the bowels, of the discourses not only of contemporary painting but of contemporary art in general.

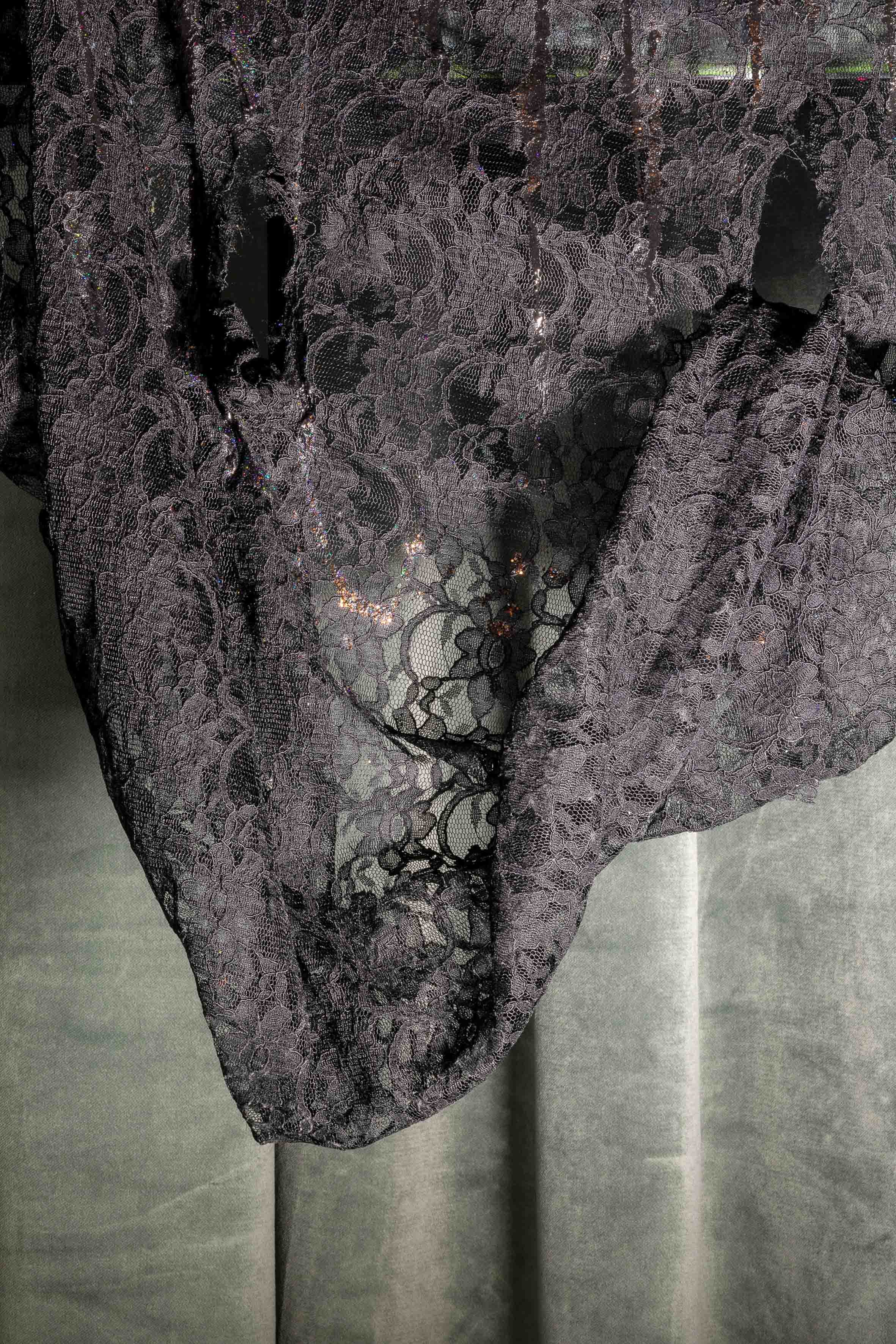

Educated at art schools in Europe and the United States, Jasmine Gregory is more than familiar with the Western art discourse. At the same time, she tells me, she also knows the social contexts in which artworks (and, perhaps, copies of famous paintings) serve mainly as decoration and are not part of said discourse, which can sometimes be laborious and theory-laden. Her work War Diaries: Will to Adorn, in which the canvas is barely recognizable as such, might well be a nod to this understanding. The same could be said of the rhinestones and glitter that Jasmine Gregory uses, things that are generally excluded or abjected (to hint at her confrontation with the notion of the abject) from the realms of so-called “high” art. The artist plays with references in a manner as virtuosic and precise as it is tongue-in-cheek. And she adds that her works with fabric—War Diaries: Will to Adorn and Struggle Porn are references to David Hammons and Thornton Dial. At the same time, Jasmine Gregory’s painting also reveals her critical distance. A distance to a western, white, and male art historiography and image production. A distance to a context that is still insanely dominant, which goes hand in hand with a reflection on her own position as a young female painter. Knowing that everything we think, say, or indeed paint is determined by the reality of our lives and that the long-present idea of a (mostly male) creativity that somehow springs from nothing is slowly but surely becoming obsolete, Jasmine Gregory radically expands her horizon of references. She sometimes uses stock images, which she digitally modifies, or photographs she encounters on social media. The detailed Martini glass painting is succinctly titled A Thing Among Things, and a (slightly adapted) line from Oscar Wilde’s novel about art and self-dramatization, The Picture of Dorian Gray, serves as the title for the painting made with oil, cellophane, and rhinestones: Never Trust a Woman Who Wears Mauve, It Always Means That They Have a History—says the hedonistic, somewhat cynical Lord Henry Wotton.

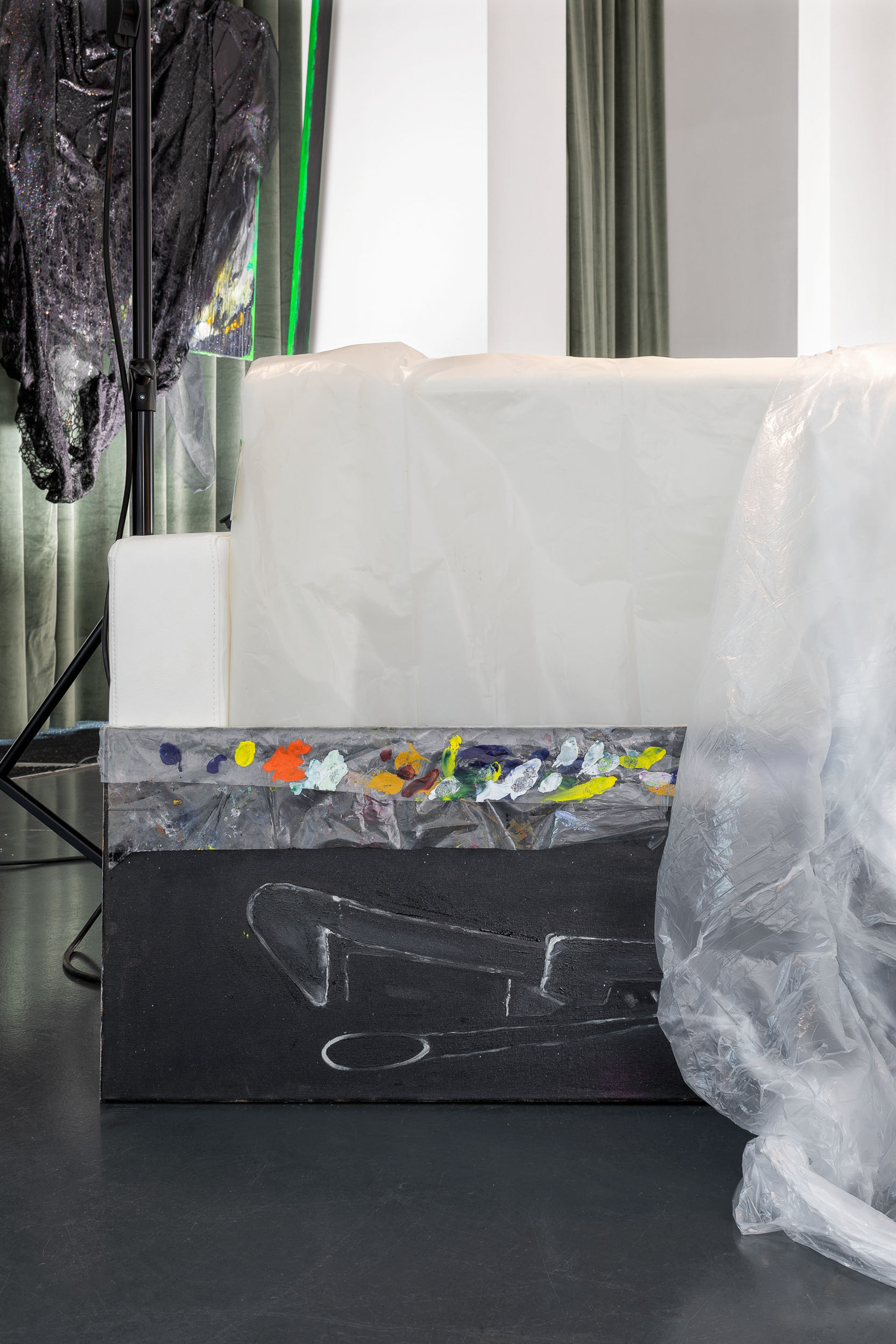

In the middle of the exhibition space, Jasmine Gregory has installed her sculpture Copy Me: Bad Clone. The sofa, which was mass-produced and ordered online, is covered with plastic foil and pieces of painted linen. The work refers to Rosemarie Trockel’s Copy Me from 2010. It is a bad clone of it, its title suggests. With Copy Me, Rosemarie Trockel addresses the reproduction possibilities of a design classic by Florence Knoll from the 1950s and the traditional attribution of the domestic sphere to women. Jasmine Gregory takes up notions of the original, copy, and clone here, with questions about legibility and a still very present Western-influenced design tradition resonating as well. Jars of dried paint are placed around Copy Me: Bad Clone on the floor. In recent months, Jasmine Gregory has been rereading works by the philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva and exploring her concept of abjection. Julia Kristeva describes the abject as anything that can evoke disgust and aversion in us (for example, corpses, spit, or pus). While the abject is always part of us and cannot be objectified, it rattles our sense of self. It represents a process of detachment and dislocation that is simultaneously essential and impossible.

Mommie dearest is the exhibition title chosen by Jasmine Gregory, referring to the 1981 film that tells the story of Christina Crawford’s painful separation from her adoptive mother, actress Joan Crawford, who is played in the film by Faye Dunaway. The jars with dried paint can perhaps be seen as the abject of Western art history and painting and, as such, an indication of the critical distancing adopted by Jasmine Gregory. An attitude that the artist illuminates dramatically in her Milan exhibition—and to which she might add a LOL. Yet, she is serious about it.

[Text: Gioia Dal Molin, Head Curator of Istituto Svizzero]

©YYYYMMDD 2021 All content and design by Daniela Grabosch + Ricardo Almeida Roque unless otherwise stated. Images, Videos and Texts can only be used under permission of the author(s).