YYYYMMDD >>> BACK HOME <<< >>> SELECTED FEATURES <<< >>> HIDDEN ARCHIVE <<<

[20220819]

LOOMING by AMALIE SMITH at HOLSTEBRO KUNSTMUSEUM [from 20220402 to 20220821]

[Photos: David Stjernholm]

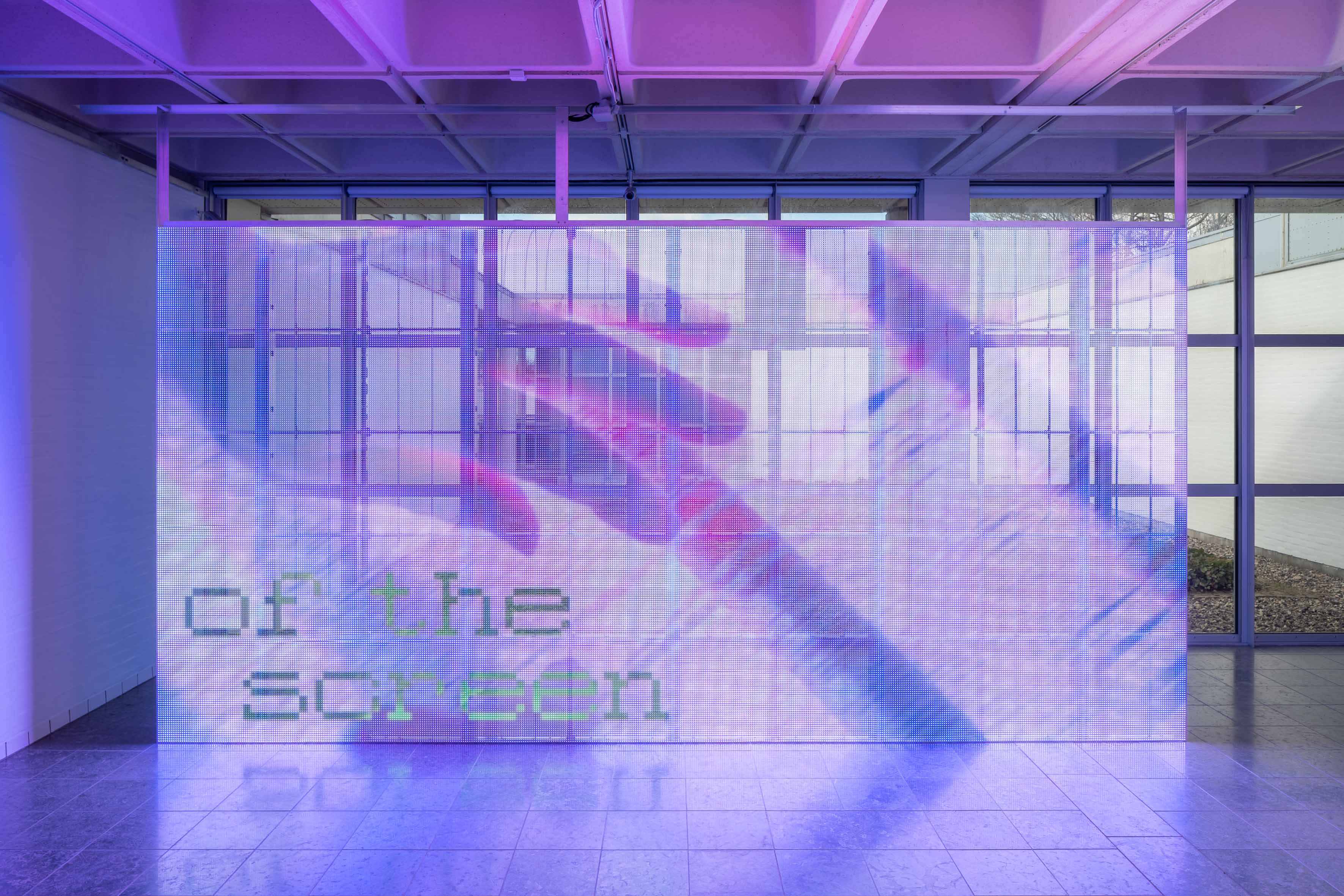

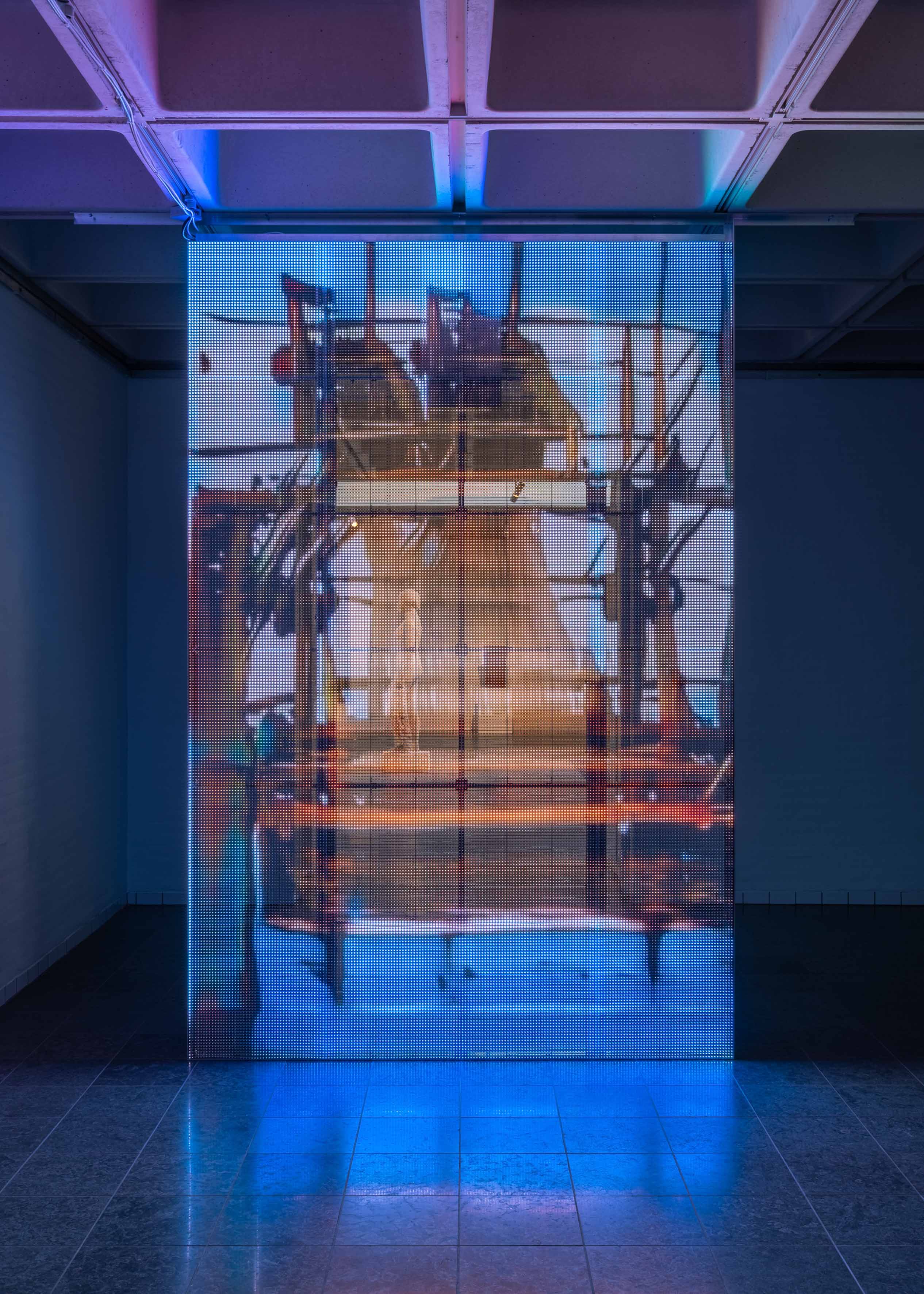

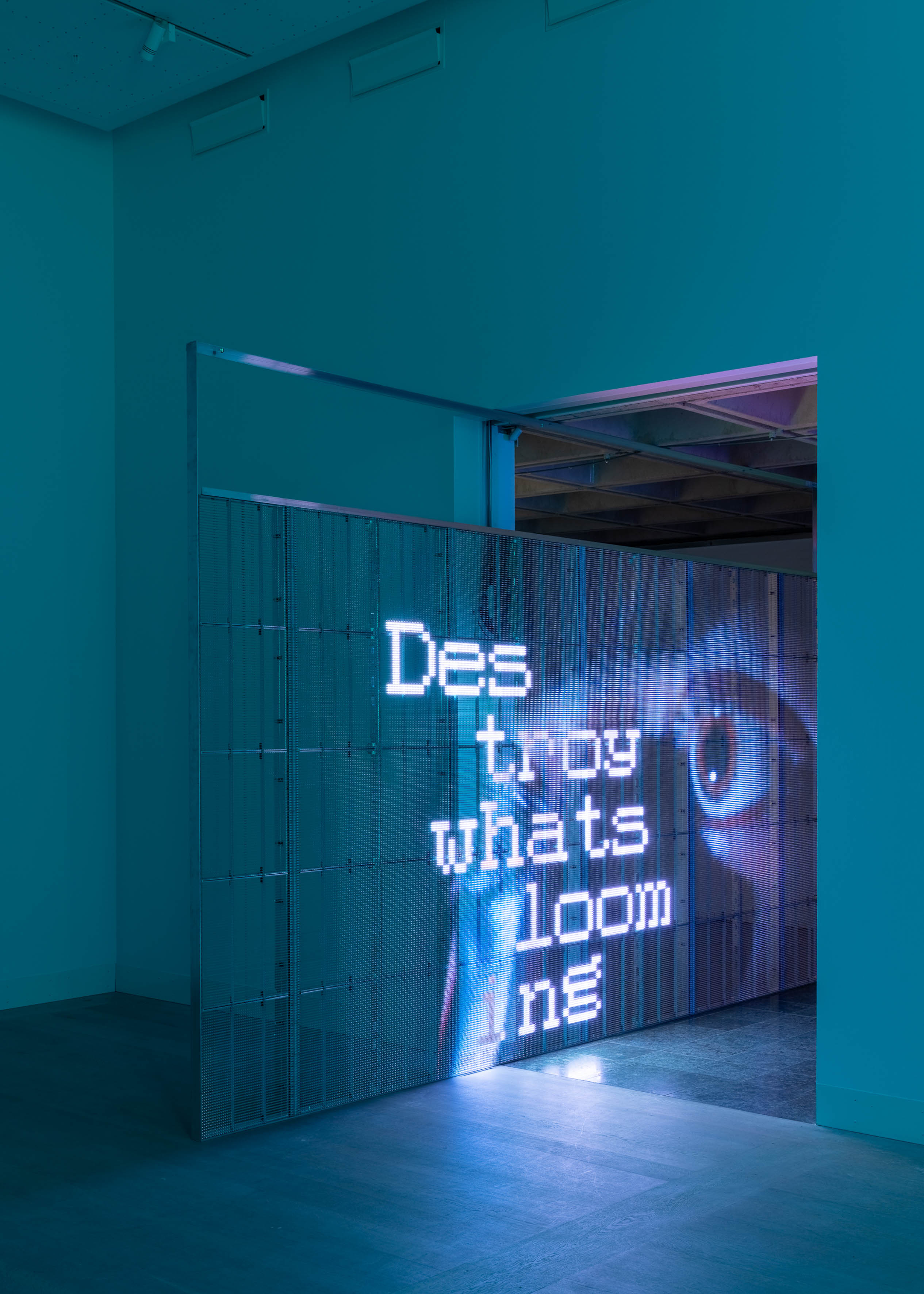

The exhibition Looming consists of five large digital screens, placed in the room sequence of the Færch Wing in the form of loosely woven fabric partitions – and it is precisely the textual quality of digital material that interests author and artist Amalie Smith (b. 1985). We often describe screen technology as intuitive and “seamless”, and when our mobile phone and computer screens display text and images instantly and almost magically, we look right through them and focus on what they present us with. But what kind of technology do the digital screens themselves represent, and what kind of images do they display?

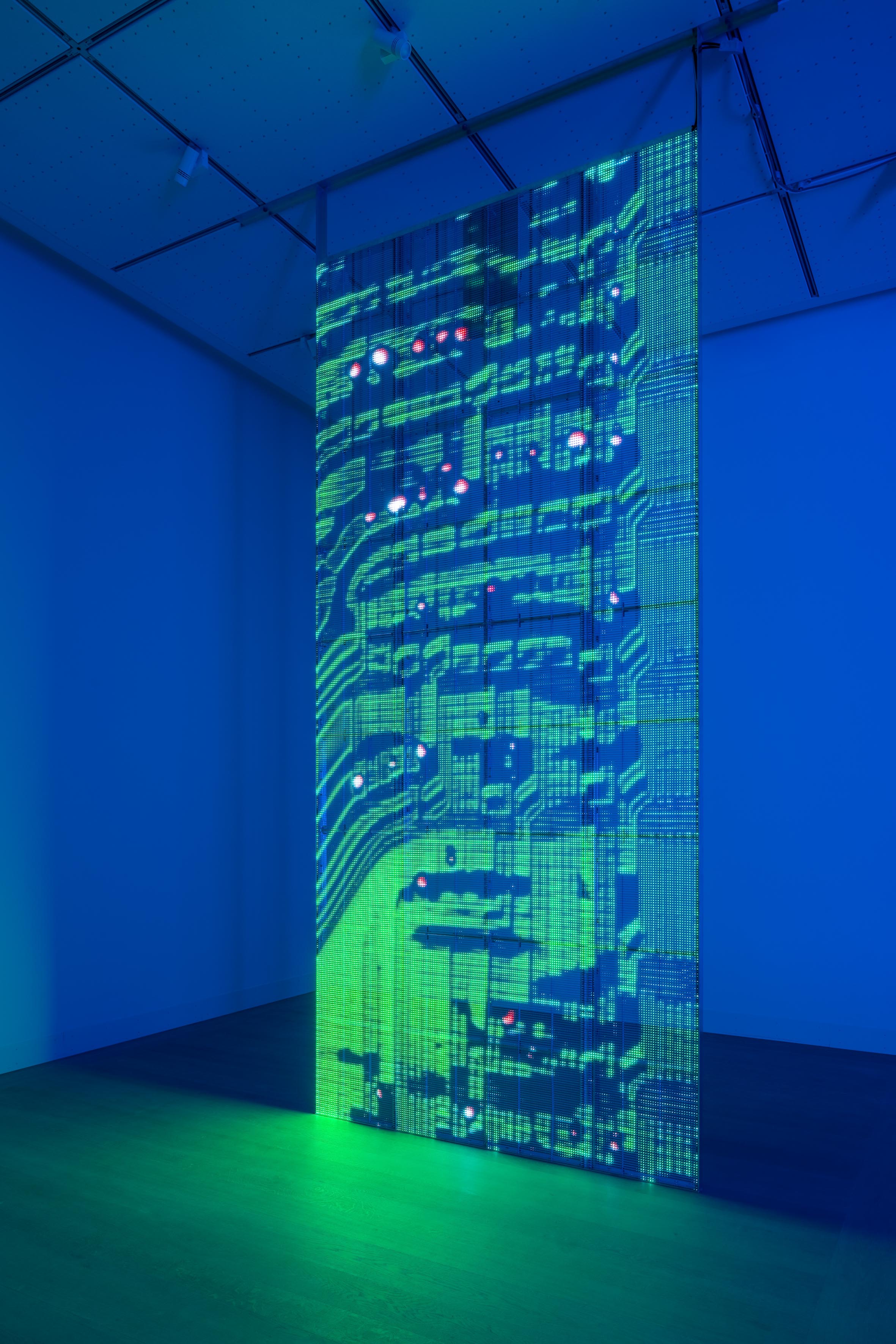

Digital technology is closely related to textile production, and thus has roots far back in the history of technology. Both the loom and the computer create images by joining up coloured points to create rows, and rows to create surfaces. Textile production and digital programs can thus both be reduced to recipes, which we also call algorithms. In the 1830s, the world’s first computer, the Analytical Machine, borrowed its punched card system from the industrial Jacquard loom that had become widespread a few decades earlier. With the punched card as the link, the loom may be understood as an ancient forerunner of the computer. For at least seven millennia, weavers have been arranging pixel patterns using binary recipes, and weaving mills were processing data long before today’s data centres were built. Even before human beings began weaving fabric, spiders spun nets, and moths spun silk cocoons.

Since the turn of the millennium, a new type of algorithm has arrived: self-learning algorithms, which are able to learn on their own, on the basis of the data you feed them. Self-learning algorithms are also called “neural networks” because they are based on simplified models of the human brain. With the advent of self-learning algorithms, the computer has begun to perceive what it displays on the screen – like a hyperloom that is able to see for itself the design it is weaving.

The screens in Looming show motifs created in collaboration with a self-learning algorithm which Amalie Smith has fed with collected photos of weaving looms, cocoon-forming insects and spindles, industrial weaving mills and data halls, textile patterns and printed circuit boards – all parts of the basic fabric of the digital world. From these photos, the algorithm has dreamed up a number of multi-dimensional pictorial spaces, each of them containing what are in principle an infinite number of new images. On the basis of samples of each pictorial space, Smith has developed a series of points, between which the algorithm has subsequently generated a journey. This is not thus a fully automated process, but an attempt by human being and machine to engage with each other in a common dream logic. The result is a kind of living picture that is not static, but constantly evolving in the direction of other, related motifs.

A metamorphosis of motif is also present in the brief film sequences that occasionally interrupt the algorithmic dreams. Here, the fabric of which the computer is made is unravelled and rewoven: Centuries-old punched card looms are illuminated like modern gaming computers, 19th-century figures are enclosed by digital image projections, and leaf-shaped insects crawl across screens. The fictional and historical muses of textile and computer technology are summoned forth: Arachne and Penelope of Greek mythology, the fictional Ned Ludd, leader of the Luddites, the military computer scientist Grace Hopper, and Countess Ada Lovelace, who devised the world’s first computer algorithm. Between each awakening and entrancement, we are guided through fragments of the data set with which the self-learning algorithm is fed.

The exhibition title Looming refers both to the loom understood as a verb, i.e. to weave, and as an adjective in the word’s original meaning, to describe something that lies threatening on the horizon. If the basic principles of the digital world were already present in the technology of the loom, what then lies latent in the digital pictorial spaces of the screens, and may unfold in future technologies? What distinguishes digital images from analogue images? What kind of life do they have – are they asleep or awake? And with the development of neural networks, could we consider our own consciousness as a kind of living imagery?

Amalie Smith (b. 1985) graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2015 and from the Danish Academy of Creative Writing in 2009. She has eight literary publications under her belt, including I civil (Gyldendal 2012), Marble (Gladiator 2014) and Et hjerte i alt (Gyldendal 2017). Her most recent publication, Thread Ripper (Gyldendal, 2020) is a multi-thread story about image weaving and computer technology. The book was nominated for the Weekendavisen Literature Prize.

Her artistic practice spans digital weaving, video installations, photography and 3D films. She has previously exhibited at, inter alia, SMK – the National Gallery of Denmark, ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, Kunsthal Aarhus, ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Kunstmuseum Bonn (DE) and the Busan Biennale 2020 (KR). In 2021, she also took part in the Soft Water Hard Stone art triennial at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York (US). Her public artworks may be seen at the premises of the Danish Energy Agency and Ørestad High School, amongst other places.

Smith has been awarded the Crown Prince Couple’s Stardust Prize (2015), the honorary grant of the Niels Wessel Bagge Arts Foundation (2016), and the Danish Arts Foundation’s three-year working scholarship (2017). She is represented in the collections of SMK – the National Gallery of Denmark, ARKEN Museum of Modern Art and Holstebro Kunstmuseum.

[Text: Holstebro Kunstmuseum]

©YYYYMMDD All content and design by Daniela Grabosch + Ricardo Almeida Roque unless otherwise stated. Images, Videos and Texts can only be used under permission of the author(s).