YYYYMMDD >>> BACK HOME <<< >>> SELECTED FEATURES <<< >>> HIDDEN ARCHIVE <<<

[20220805]

IN THE PLACE OF ANNIHILATION, WHERE ALL THE PAST WAS PRESENT AND RETURNED TRANSFORMED by AZZA EL SIDDIQUE at MIT LIST VISUAL ARTS CENTER organized by SELBY NIMROD [from 20220630 to 20220904]

[Photos: Mel Taing]

The MIT List Visual Arts Center opens Azza El Siddique’s debut institutional solo exhibition on June 30. The exhibition marks the 25th iteration of the List Projects exhibition series and will present a newly commissioned installation by the artist.

Azza El Siddique (b. 1984; lives in New Haven, CT) is known for room-sized sculptural environments that take up the related themes of entropy, impermanence, and mortality. Her works engage multiple senses, and feature materials that are recast by time and elemental forces, like water, light, and heat. In past works, she has outfitted austere metal constructions with heat lamps that diffuse scents like sandalwood, and slow drip irrigation systems that erode sculptures in unfired clay. These aromas and materials evoke both Islamic mortuary rituals and the artist’s sensorial recollections of her adolescence in a Sudanese community in Canada. Recently, El Siddique has become drawn to the cultural and economic significance of scent in ancient Nubia and the neighboring Egyptian Empire, investigating the related histories and myths that endure in Sudanese culture.

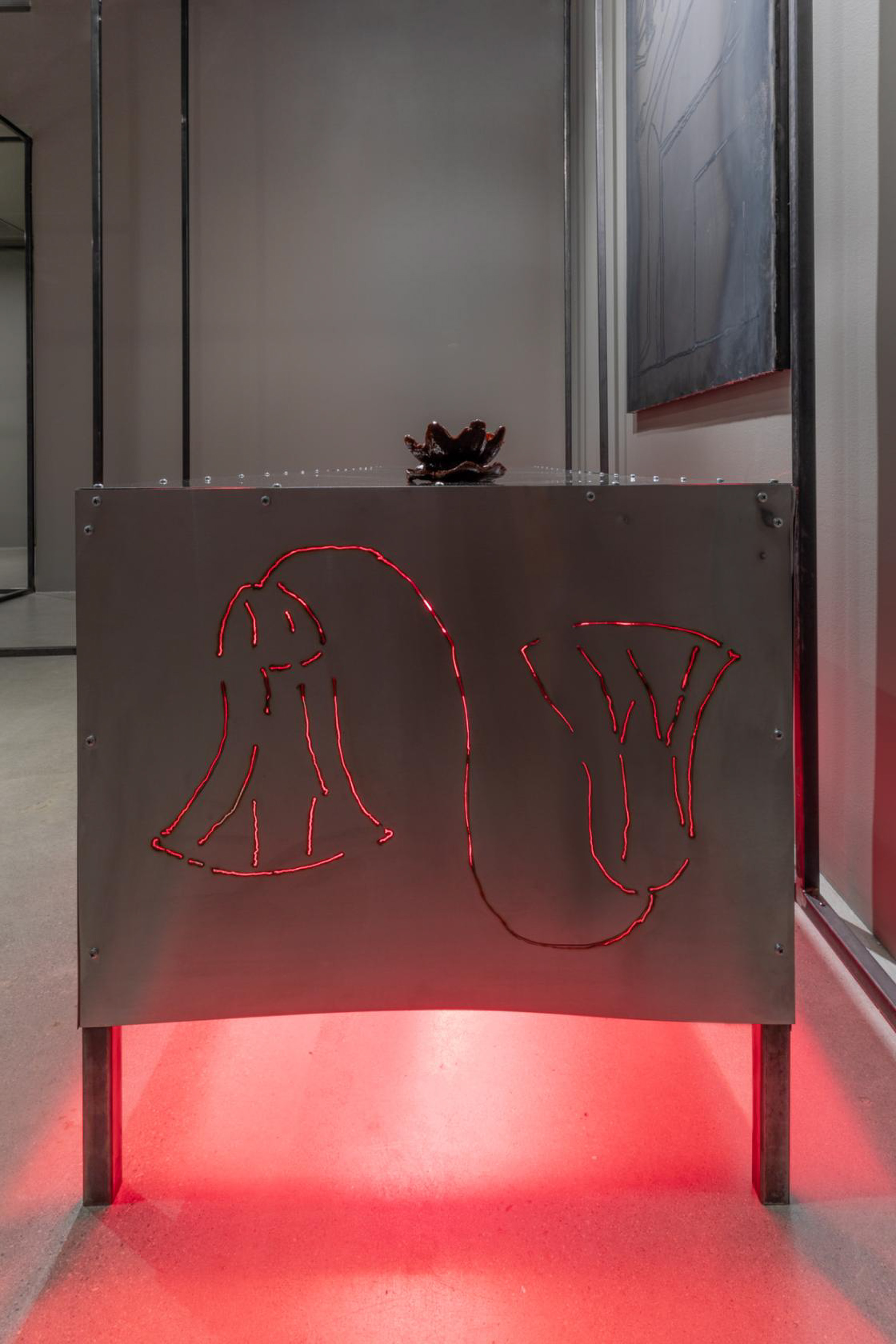

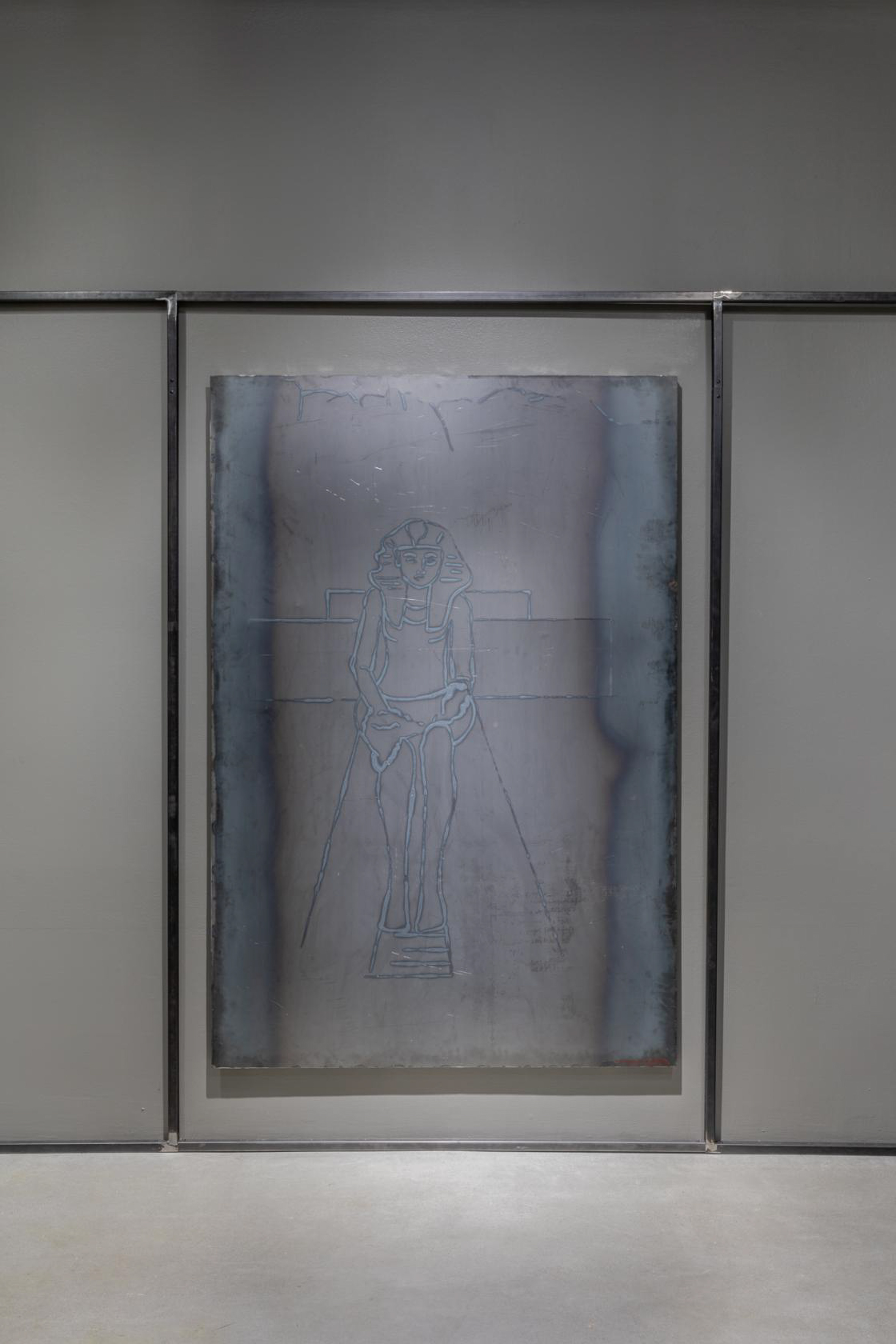

For her first museum solo exhibition, El Siddique debuts In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed (2022), a site-specific installation that uncovers the personal, ancient, and colonial narratives of the fragrances used in bukhoor. Ubiquitous in Sudanese and diasporic Sudanese households, this incense is a blend of sandalwood chips, aromatic resins, and European perfumes made for export to North African markets, all bound together with sugar. In El Siddique’s installation, bukhoor incense cast into the form of waterlily blossoms is incrementally heated, permeating the gallery with scent and eventually melting until only a sticky residue remains. The installation’s steel architecture is based on the floorplan of a temple dedicated to the shape-and gender-shifting ancient Nubian god of incense, Dedwen, and houses drawings welded on steel panels as well as a two-channel video mapping the chemical compounds of bukhoor’s various ingredients. The video’s 3-D scans of eerily floating mounds of frankincense and other fragrant resins allude to the historical trade networks of these aromatics, and their use in religious ceremonies that doubled as displays of political power.

El Siddique likens the slowly unfolding events in her works to the subjective and unstable production of historical narratives and personal recollections. The work’s atmospheric evocations of the long, multilayered histories of ancient sites, precious resins, and traditions highlight how, in the artist’s words, “lineage and inheritance keep moving through systems” that are re-formed with the passage of time.

List Projects 25: Azza El Siddique is organized by Selby Nimrod, Assistant Curator.

Azza El Siddique (b. 1984 Khartoum, Sudan) lives and works in New Haven, CT. Previous solo exhibitions include Begin in smoke, end in ashes, Helena Anrather, New York; let me hear you sweat, Cooper Cole, Toronto, ON; Concave Conflux Convex, Harbourfront Centre, Toronto; Lattice be Transparent, 8eleven, Toronto. Her work has been included in group exhibitions at MOCA Toronto; Gardiner Museum, Toronto; Oakville Galleries, Toronto; Shin Gallery, New York; Green Hall Gallery, New Haven; Towards, Miami; and Parisian Laundry, Miami. El Siddique received an MFA from Yale University School of Art in 2019 and a BFA from Ontario College of Art and Design University in 2014. She was a Skowhegan resident in 2019.

Brouchure text:

Azza El Siddique is known for her room-sized sculptural environments made of welded steel that take up the related themes of entropy, impermanence, and mortality.

Reflecting the transitory nature of these subjects and experienced with multiple senses, works by the Sudanese- Canadian artist feature materials recast by time and the controlled exertion of elemental forces, like water, light, and heat, until only residues remain.

El Siddique’s modular, architectonic steel forms are based on the floorplans of ancient Nubian sacred sites, including ritual and funerary temples. Calling on her inheritance of traditions that originated in these spaces, she reconstitutes them with contemporary industrial materials as enveloping monuments to transience. Often, the purpose-built architectures support smaller sculptures of vases, urns, and fragmented figures rendered in glass and unfired ceramic. In installations like Begin in smoke, End in ashes (2019) and Measure of one (2020), water droplets released through slow-drip irrigation systems gradually erod the clay objects and oxidize the steel. Through this dynamic, time-based material system, elements of her works undergo an entropic transformation— from creation to dissolution. The artist has also outfitted her austere metal constructions with heat lamps diffusing the scent of sandalwood, an arom that evokes both Islamic mortuary rituals and sensorial recollections of her adolescence in a Sudanese community in Canada. El Siddique likens the slowly unfolding events in her installations to the subjective, unstable, and mutable production of historical narratives and personal recollections.

Recently, El Siddique has become drawn to the cultural and economic significance of scent in ancient Nubia and the neighboring Egyptian Empire, investigating the lineage of aromatic materials that continue to play important roles in contemporary Sudanese culture. At the List Center, her newly commissioned work, In the place of annihilation, where all the past was present and returned transformed (2022), uncovers the intertwined, personal, ancient, and colonial narratives of the fragrances used in bukhoor. Ubiquitous in Sudanese and diasporic Sudanese homes, this incense is made from compressed sandalwood chips, a blend of precious aromatic resins (including frankincense, amber, and oudh), Sandalia (a sandalwood oil perfume), and European scents made for export to North African markets, all bound together with sugar. While bukhoor is commercially available, there are many homemade variations, and El Siddique studied traditional recipes to develop the incense that serves as a sculptural medium in this installation.

Small bukhoor sculptures in the form of waterlilies are incrementally heated and will gradually combust, permeating the gallery with scent and eventually melting until only a sticky residue remains. The waterlily is associated with Dedwen, a shape- and gender- shifting Nubian god closely associated with the natural resources of Nubia and incense, in particular. [1] With this subtle reference to the mythic Dedwen, who was said to smell of burning incense, the cast bukhoor blossoms are placed within the framework of an immersive steel architecture based on the floorplan of the deity’s birth house in the Temple of Kalabsha grounds. [2]

The artist’s structure also houses a two-channel video mapping chemical compounds of the various ingredients that comprise bukhoor incense. A sort of digital recipe, the video’s 3-D scans of the topographies of eerily floating mounds of frankincense and other fragrant resins also allude to histori- cal trade networks. Ancient Nubia’s premier exports to pharaonic Egypt were the aromatics used in ceremo- nies “connected to the inseparable realms of religion and politics,” which intricately linked them with displays of state power. [3] El Siddique summons these entangled histories in illustrations welded onto the installation architec- ture. Formed by a metallurgic alchemy of concentrated applications of heat and gas (she employs a combination of MIG and TIG welding techniques to render loose, expressive sketches on polished stainless steel panels), her drawings include pictorial homages to precious aromatic resins and their chemical makeup, the artist’s inter- pretations of the narratives of ancient creation myths, and iconographic ref- erences to Hatshepsut, a “female king” in pharaonic Egypt. The latter, keenly aware of the power conferred by both representation and religious ritual, pre- sented herself with masculine features and kingly regalia in commissioned por- traits that glorified her rule, particularly her role in organizing trade expeditions, which brought frankincense and myrrh to Egypt for ceremonial use. [4]

The “annihilation” El Siddique references in the installation’s title aligns less with the word’s colloquial usage as complete destruction than with annihilation as a principle in physics—where the force exerte by subatomic collisions converts matter into energy (when two particles collide at speed, for instance, they “annihilate” into photons with mass identical to that of their previous form). Physical state changes akin to annihilation are found throughout the work’s materials and techniques, from the combustion of cast incense to the residual heat ripples that form the linework of her metallurgic drawings. The transformative resonance of annihilation also offers a metaphor for the sensorial historiography present in the work’s consideration (and collapse) of past and present relationships between scent, memory, and power. El Siddique’s atmospheric evocations of the long, multilayered histories of ancient sites, precious resins, and traditions she carries into the present highlight how, in the artist’s words, “lineage and inheritance keep moving through systems” [5] that are re-formed with the passage of time.

[1] Pearce Paul Creasman and Kei Yamamoto, “The African Incense Trade and Its Impacts in Pharaonic Egypt,” African Archaeological Review 36 (2019): 349.

[2] The Temple of Kalabsha was erected around 30 BCE near what is now the city of Aswan in southern Egypt. In 1970, after the construction of the Aswan High Dam, the temple was relocated to higher ground to protect it from flooding. It was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

[3] Creasman and Yamamoto, “The African Incense Trade,” 358.

[4] Uroš Matić, “(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 23 (2016): 813.

[5] Azza El Siddique, “Creative Conversations: Azza El Siddique, Nour Bishouty and Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum,” MOCA Toronto, October 14, 2021, https://moca.ca/events/creative- conversation-azza-el-siddique-nour-bishouty-pamela-phatsimo-sunstrum/.

[Text: Selby Nimrod]

©YYYYMMDD All content and design by Daniela Grabosch + Ricardo Almeida Roque unless otherwise stated. Images, Videos and Texts can only be used under permission of the author(s).